(with contributions from Alan March)

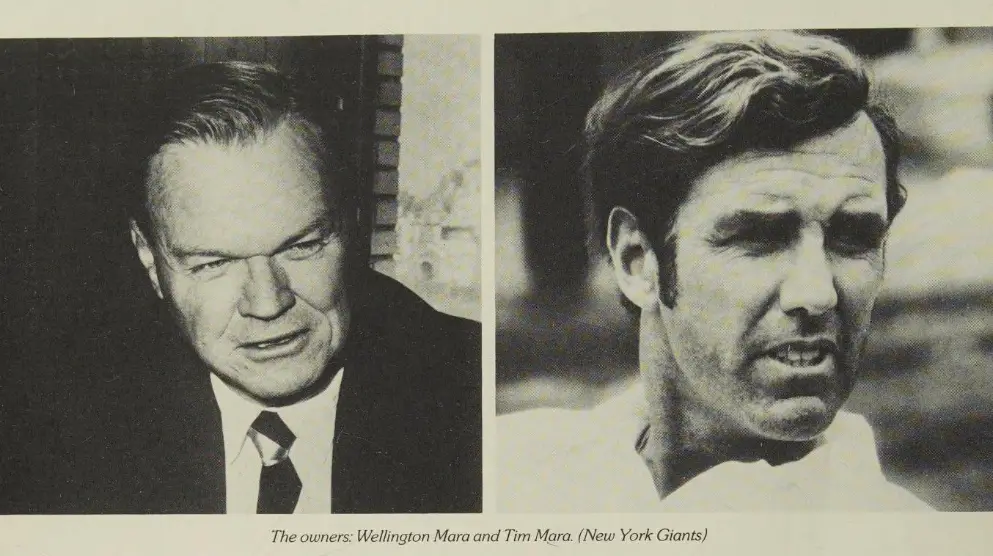

The New York Football Giants, who celebrated their 100th season of play in the National Football League in 2024, are noted for having their franchise continuously headed by the Mara family. The Maras have had at least 50 percent ownership of the flagship franchise for the entirety of their existence, and owned the club exclusively for most of their first 65 years.

However, since the late 1990s, one key member of the Mara family has been either forgotten or outright excluded from any official telling of the Giants history: Timothy J. Mara II, who owned half of the franchise from 1965 through 1991 when he sold his interest in the team to Bob Tisch.

Tim Mara’s tenure as both owner and board member spanned the most tumultuous era in the team’s history – a period marked by the nadir of its on-field struggles, later dubbed “The Wilderness Years,” the franchise’s move from New York to New Jersey, and a highly-publicized internal power struggle that erupted on New Year’s Eve in 1978. Despite these challenges, this era ultimately laid the groundwork for the team’s resurgence and a second golden age beginning in the mid-1980s.

While his tenure was not the longest in the franchise’s timeline, it may have been the most significant.

The Founding

The Giants’ founding father was the first Timothy J. Mara, grandfather of the latter. In May of 1925, Mara had gone to visit his friend, boxing promoter Billy Gibson, to discuss a share in boxer Gene Tunney. Also at Gibson’s office was National Football League president Joe Carr. Mara was a bookmaker who made his way primarily at the racetracks, and he had a keen interest in boxing. Upon learning that Tunney was unavailable, Mara and Gibson were persuaded to invest in a new team by Carr and Dr. Harry A. March, a pro football veteran of the pre-NFL days in Ohio who had served as the team physician of the Canton Bulldogs and was regarded as an expert in team organization. While a price tag of $500 for a professional football team may seem laughable in the 21st century, it was no small sum in 1925. Mara took on Gibson and March as co-owners.

While Gibson was officially known as “President,” he had minimal involvement with the team and was mostly a silent partner. Tim Mara, as “Treasurer,” used his notoriety and influence in New York to secure a prime location at Harlem’s Polo Grounds and to run promotions to draw fans and stimulate interest in the fledgling league. March, the team’s “Secretary,” organized the talent, hired coaches and advised Mara on how to field a competitive post-graduate football team.

Following a calamitous 1926 campaign that saw the Giants and NFL ward off a rogue start-up league known as the American Football League, Gibson decided he’d had enough with pro football and sold his interest in the team to Mara to focus on boxing, where he had successfully promoted the Gene Tunney-Jack Dempsey fight in Philadelphia that September. Mara assumed the title of “President” while March remained “Secretary.”

Mara and March ran the Giants as a duo until November 1932 when March sold his 10% stake to Mara, making Mara the sole owner. However, Mara, who was involved in lawsuits regarding his boxing interests, transferred ownership of the team to his two sons, Jack (age 22) and Wellington (age 14) in 1930.

Jack, who is believed to have been mentored by March for several years as an executive-in-waiting, first appeared on the franchise’s masthead in 1930 as “Vice-President”, then “President-Treasurer” beginning in 1931. The younger Wellington arrived as “Treasurer” in 1938.

Regardless of titles, the division of duties between the two brothers was significant, as it shaped the way the Giants’ operations have been run in perpetuity. Jack handled the financial and promotional functions while Wellington headed the football operations. This dualistic, two-headed-coin philosophy of running the franchise continues to this very day.

While on paper Jack and Wellington each owned 50 percent of the franchise, Tim was omnipresent as an overseer and advisor. Tim Mara I passed away early in 1959, not long after the Giants legendary championship bout with the Baltimore Colts. This game became known as “The Greatest Football Game Ever Played” and vaulted pro football into the forefront of the public’ consciousness.

With Tim’s death, the two brothers truly ran the show on their own. Jack’s son, Tim Mara II, joined the management team as “Secretary-Treasurer” prior to the opening of the 1959 football season, while Jack and Wellington assumed the titles of “President” and “Vice-President,” respectively. By all accounts, this arrangement ran well during its 6-year duration.

Transition

The death of Jack Mara in June 1965 reverberated throughout the organization, and altered the Giants’ functionality for the next 14 years.

Although the two brothers occasionally disagreed on team decisions, their business relationship was never truly disharmonious. Years later, Wellington even admitted he had viewed his older brother as a father figure and often deferred to Jack’s judgment.

After Jack’s death, Wellington’s decision-making can be viewed in hindsight as reactive. As the sole acting owner, he was free from any system of checks and balances. The reordering of the hierarchy saw Wellington as the new “President,” a title that he would regard in the strictest literal interpretation, and his nephew Tim as “Secretary-Treasurer.” The two stewards of the Giants had work ethics as diverse as their personalities and lifestyles.

Wellington’s response to his brother’s absence was to take on more responsibility; he now oversaw more than just the team’s management. He took an ever-growing role in the NFL’s interests in the battle with the AFL, in negotiating television rights, and a potential labor dispute with the player’s union. He took a keen interest in all of the financial responsibilities for the Giants as well.

To create a sense of stability, Wellington pursued a path of continuity. In July, he extended the contract of head coach Allie Sherman to a new 10-year contract that superseded his existing five-year deal. At least part of his reasoning for re-signing Sherman may have been to silence rumors that the Giants would not be able to remain in the Mara family following Jack’s death, which Wellington denied.

While Wellington spread himself thinner than ever, Tim was seemingly detached from the Giants’ operations, giving the impression that he was irresponsible at best, indifferent at worst. He was often late to the office, performed mostly menial tasks, and spent most evenings carousing in Manhattan nightclubs during the week while spending weekends at either of his houses on the Jersey shore and Florida. Wellington, of course, was present at the Giants’ office or practice field, NFL offices in mid-town Manhattan, and his home in nearby Westchester County. Two more divergent personalities they could not be, and Tim’s casual lifestyle irritated Wellington from the get-go.

In the summer of 1969, Tim II began to step-up and show engagement and a sense of responsibility, at least professionally, when the Giants received overtures from the state of New Jersey with regard to the building of a proposed sports and entertainment complex of which the Giants would be the cornerstone. The Giants’ lease at the aging and somewhat run-down Yankee Stadium was due to expire in 1974, and the financially strapped City of New York had not been allocating resources into the upkeep of the renowned ballpark. The long-term hope of the New Jersey officials was that by luring the Giants across the Hudson River, the Yankees would soon follow, giving them the crown jewels of New York’s professional sporting universe.

Little was written about the Giants potential move until the grand announcement in August 1971 that a deal had been signed and the schematics for the new Meadowlands project was presented for all to see. While the political grandstanding and rhetoric proclaiming outrage and disloyalty was to be expected, this was clearly a great deal for the Giants that would allow them to prosper as they never had before. Having spent their first 45 years as tenants in baseball parks, the Giants would own their own home in a state-of-the-art facility designed specifically for football.

Although Tim was the driving force behind all of the negotiations, design, and building of Giants Stadium, Wellington was the public face of the franchise at the press conference and all follow-up communications.

While 1971 was a successful year for business, the 1971 season was an on-field disappointment. The Giants failed to follow-up their winning 1970 season. Along with another losing season, there was off-field tumult. During training camp, quarterback Fran Tarkenton and Wellington disagreed over an exchange of funds that Tarkenton had assumed was a bonus and Wellington insisted was a loan. Whether Tarkenton’s play dropped off because of the financial dispute is not known, but Tarkenton’s lackluster performance saw the Giants sink in the standings.

The New York Post published a series of anonymously quoted articles, titled “Maranoia” and penned by Larry Merchant, that were a scathing indictment of the Giants’ operations. While at the time Fran Tarkenton was the suspected leaker, it was later revealed that Fred Dryer was actually the source of the leak.

The series claimed that Wellington ran the Giants very much as he had done in the 1940s, including children running around the practice field and even the locker room on game day. Merchant said, “Poor Wellington Mara. He is a man in future shock. His code of old-fashioned loyalty and Boy Scout morality, however virtuous, is irrelevant in modern football.” He also quoted a player (likely Dryer), “They’re living in a dreamland.”

Merchant also named players who “want out now: Tarkenton, Dryer, Jim Kanicki and Carl ’Spider‘ Lockhart.”

Critiques of Wellington were not relegated to New York papers. A 1972 feature article in Sports Illustrated, Wellington was also painted as a thin-skinned individual with little tolerance for criticism. During the season, defensive end Bob Lurtsema was released from the team on the very day he gave a report to Wellington about the players ”opinions of Wellington and the Giants’ operations.” Lurtsema said, “He asked for an honest report, and I gave it to him with both barrels. I told him, ‘You have no rapport with the players, and the Giant Family image is not there. There is no question about it.’ He was crushed when I told him. I wasn’t trying to hurt the guy, but to tell him the truth he asked for. He sat back, maybe asked me a couple of questions and then shook my hand and said, ‘At least I know you gave me an honest answer.’ At 4:30 I was on waivers.”

Complicating the issue was that Lurtsema was also the Giants players’ union representative. Wellington was known to have a grudge against the Union. He had felt the players should feel privileged to be a part of professional football and resented the way the league had become more business-oriented since the influx of wealth from network television money arrived in the previous decade.

Wellington resented how growing labor issues drew him away from the Giants and more toward the league office. In July 1974, as the league stared down the possibility of its first ever work stoppage, Wellington said, “I’m going to have either an ulcer or heart attack and 20 extra pounds by the time this is over…I’ve only been to practice four times. I’ve always hated to miss practice.

“In the old days, a football team was a one-man show. There was a head coach, who ran the team, and the assistants were really assistants and no more. Now it’s a chairman of the board and a lot of executive vice presidents. I suppose that filters down to the players…They’ve chosen to play football, and I just think their freedom comes in making the choice for the career they want. Once you’ve done that, you must accept the limitations of that career in exchange for the rewards it will get you.”

Giant veteran Dan Goich said of his owner, “He takes everything so personally. I don’t think he’s sincere. It’s more like he’s out to get back at the people who are messing with his little toy.”

An anonymous player added, “It’s not that the game is a religion to him, it is a religion. In the middle of everything he’ll stand up, with that weirdly contorted face of his, and hold up the NFL manual like a bible and say, ‘It’s right here. You can’t change that.’”

An unnamed Giants assistant coach said, “(Wellington) is one of God’s greatest people, but he doesn’t have any idea of what it takes to play winning football today. He just won’t let go.”

All of this highlights the significant difference between Wellington and Tim. For Wellington, who had grown up with the Giants, they were a part of his life and there was no distinguishing between family and business – the Giants were his family. On the other hand, Tim was very much a pragmatic executive who kept work and his personal life separate.

Half Measures

Perhaps at least partly in response to outside criticism and restoring his image, Wellington hired former Giant great Andy Robustelli as the Giants’ new Director of Operations. Although unacknowledged at the time, Tim influenced the decision. Years later Wellington recalled, “Tim was very dissatisfied with a lot of the football decisions I had made, and in retrospect, they weren’t very good ones. He said I was trying to do too much and suggested we get a football man to run that end of things…I started running the football and business sides of the team when my brother Jack died, to the detriment of both. Part of the problem was that I had been very involved in league matters and was away a lot of the time.”

While on the surface this appeared to be a significant step back by Wellington to turn over the football decision-making responsibilities, there were those who doubted how much of a change this would really be.

For his part, Robustelli appeared satisfied with the arrangement, “I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have the full authority to get the ball club where it should be. Wellington Mara gave me his word I’d have full authority…I told Well there would be times I won’t want the kids in there and he told me, ‘Whatever you say.’”

Wellington said, “I won’t have any decrease in responsibility, but I will have a decrease in duties.” He also seemed to acknowledge the need for organizational change. “It’s an odd thing, but I don’t have much experience in picking coaches. They were all at hand. Steve Owen was here when I got out of college and Jim Lee Howell was promoted from assistant. So was Allie Sherman when I couldn’t get Vinnie Lombardi and Alex Webster was a battlefield promotion of sorts. Now we’re facing something new and different.”

An anonymous associate of Wellington said, “Wellington believed that the extended family system could still work in the modern era, and without his father or Jack around to fall back on, he brought in Andy not so much as a general manager, as a kind of surrogate older brother.” Likewise, an anonymous NFL general manager said, “Football was moving from the patriarchal era of the Halases and Rooneys and Maras into a highly sophisticated sport, and the Giants were remaining a family operation.”

Robustelli said, “The (1970) merger undid all the things the NFL had been at that time. It had been a fraternity of good owners who would trade honestly, because they had to deal with one another all the time and there were only 12 of them. After the merger, you did business in a cold, calculating world. (Owners) didn’t give a damn about the league anymore. They cared only about their own team, a profit, winning to keep the fans. And that’s the reality. That’s the times now.”

Robustelli’s choice for head coach was Bill Arnsparger, the hot assistant who had gained enormous respect around the league as the architect of Miami’s renowned “No Name Defense.” In his two-and-a-half seasons, Arnsparger navigated the Giants through a tumultuous time. The Giants played their home games in three different states, and Arnsparger was fired after a miserable 0-7 start to the 1976 season.

The opening of Giants Stadium in October of that year was an unparalleled success. Even the one-time detractors from the east side of the Hudson River exalted the excellence of the brand new, state-of-the-art facility and predicted future success for the team there. But the on-field results were predictably poor. During the pre-game ceremonies—featuring introductions of players from the 1925 and 1956 Giants teams—the running joke among the press was that the struggling 1976 Giants could have used those former players in uniform.

Part of the lack of talent that continued to plague the Giants was due to the amount of resources allocated to sign free agent fullback (and Super Bowl MVP) Larry Csonka. Csonka became available when the rival World Football League folded. He demanded compensation as a premiere talent, despite now being an older player who was showing some wear-and-tear and having played two seasons on a mediocre team.

The issue of how to handle the influx of refugee players from the failed league dominated the owners’ meetings throughout the offseason. The central debate was whether the NFL teams those players originally came from—such as Csonka’s—were entitled to compensation from the teams signing them. There were strong advocates on both sides, with Wellington supporting the pro-compensation stance: “My gut feeling is we owe something to Miami for Csonka and Art Modell (Cleveland Browns owner who signed Paul Warfield) thinks so too. But my feeling is also that we’re not going to pay anything to Miami until Washington (who had signed Calvin Hill) pays Dallas.”

Despite most owners agreeing that compensation was “the right thing,” very few displayed the gumption to act on it. Modell said, “There is no solution,” and acknowledged that he and Wellington, “feel a moral obligation to the Dolphins that may not be solved.”

Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, Wellington stood by his principles and sent two third-round draft picks (one in 1978 and one in 1979) to Miami, despite his detractors’ consternation. “When Larry was in New York to sign, I promised (Joe) Robbie and (Don) Shula that we would compensate them. I know we didn’t have to do it, and I don’t expect this to open the door for other teams to offer compensation, but I wanted to do it.”

An unnamed Giants staff member said, “Confucious say: honorable man get taken in the end. But I tell you, it’s nice working for a guy like that, and I just hope nice guys don’t always finish last.”

The Giants tapped John McVay, a WFL refugee, to replace Arnsparger as coach. After a 3-4 finish and positive reviews from the players, the Giants signed him full time at the end of the season. Despite improved drafting and upgraded facilities, the Giants continued to lose more often than they won, and the culture failed to improve. Disgruntled tight end Bob Tucker went public with his dissatisfaction and ultimately forced the Giants to trade him to Minnesota during the 1977 season. After the trade, Tucker did not hold back, “It was abysmal – the coaches were unprofessional. (When he arrived in Minnesota) was like I’d died and gone to heaven. I was back in the football business…It was thrilling.”

Unbeknownst to the public, internal friction was brewing beneath the surface as these events unfolded. With Giants Stadium now operational and widely praised as a premier sports facility, Tim—experienced and successful on the business side—had grown frustrated with the team’s continued losing. He began voicing dissenting opinions on football matters, a move that surprised many within the Giants’ inner circle and struck some as disrespectful. For the first time, Tim had crossed from business into what many saw as unwelcome territory. He let it be known that he was opposed to the signing of Csonka and was frustrated that not only were his concerns unheeded, but that his status as 50 percent seemed to carry no weight within the organization.

While outsiders may have been blissfully unaware of the building tension within the offices at Giants Stadium, Robustelli had been caught in the middle of the bickering uncle and nephew and had grown weary of his untitled role as diplomat. During the offseason, he sent a memo to both owners stating his intention to retire following the 1978 season.

As it was following his brother Jack’s passing in 1965 when he signed Sherman to the 10-year contract, Wellington’s response was to maintain continuity. He chose Terry Bledsoe from the league office to be assistant general manager, much to the chagrin of Tim, who was not consulted on the move. Tim interpreted this as a surreptitious attempt by Wellington to maintain his influence over the organization.

Years later Robustelli admitted, “In retrospect I didn’t know or realize how far behind we were as an organization. We needed to overhaul the entire organization. But I realized it had to be done within the framework of its president, who wanted to be loyal and faithful to certain people, as well as a vice-president who had similar loyalties. Clean house? No way!”

Rock Bottom

The events of November 19, 1978 marked the lowest point in the Giants’ first 100 years in terms of on-field performance, when they literally fumbled away a 17-12 victory against the Philadelphia Eagles. New York chose to run a handoff instead of a quarterback kneel-down with under 30 seconds to play, which proved disastrous when Joe Pisarcik and Larry Csonka botched the handoff and Eagles Herman Edwards recovered the loose ball giving Philadelphia a miraculous win in stunning fashion.

‘The Fumble,’ in hindsight, became a necessary catalyst for change, ultimately ending the franchise’s infamous “Wilderness Years.” However, before the team’s fortunes could turn, its off-field management had to hit rock bottom. Although the on-field product was eventually redeemed, the internal family rift caused by it would grow into a permanent divide.

The fans certainly made their voices heard. Over the final two home games they sent their message to management in the most public of ways: an organized burning of tickets outside the Giants Stadium gates and a plane circling the stadium with a banner reading “15 YEARS OF LOUSY FOOTBALL WE’VE HAD ENOUGH”.

A season ticket-holding protester said, “We’ve got a message to get across to Mr. Mara. This stadium is beautiful. Everything here is professional, but the team.” Another added, “This team needs to spend some money, get a different philosophy and get the right people to run the show.”

One Giant veteran, Brad Van Pelt, showed empathy, if not total agreement, “Giant fans are the greatest in the world, they’re just showing their displeasure. They want a better performance on Sunday, and they deserve one.”

A portentous innuendo penned by the Newark Star-Ledger’s Jerry Izenberg the day after the banner flew over the stadium was the first real indication of what was to come: “Publicly, there is a tendency ‘not to dignify’ the current fan revolt which has yet to lift a dime out of management’s wallet. There is a tendency to cast doubt upon the revolt’s ability to match bodies for noise.

“That’s publicly.

“Internally, it’s not so casual. For all the scorn heaped upon Wellington Mara by the legion of justifiably frustrated, it is surely not his intention to lose football games. He is a victim of inertia compounded by loyalty. Now, the corporate relationship between Wellington (president) and his nephew Timmy (vice-president) is said to be headed toward a power struggle.

“When management says it has not talked to anyone about the sensitive role of general manager or operations director or whatever the new seat of power will be called, bear in mind that management has four stockholders – Timmy, his sister, Moira, their mother Helen (widow of Wellington’s brother Jack) and Wellington.

“For the first time ever, the sound of the wounded fan is being heard in the corporate offices. The previous firings were a Band-Aid on a broken leg. The forces leading to this particular showdown are something else.”

A week after the final game of the season, McVay was fired and Robustelli resigned as planned. Wellington said, “Our next move is to decide what our next move is. I don’t close my mind to anything, whether it means hiring two men or one for both jobs. I guess we’ll come up with lists.”

That sounded good enough on the surface, but this is where the Giants became stuck for nearly two full months. Despite Wellington’s statement of being open-minded, the two owners were steadfast in their beliefs on reshaping the organization. Wellington favored hiring a coach and promoting Terry Bledsoe for the director of operations position vacated by Robustelli. Tim wanted to reach outside the Giants family, bring in a strong general manager, and have him choose his own coach.

Neither showed any willingness to compromise.

Robustelli said years later, “During my five seasons as director of operations, the games played behind the games played on Sunday were far tougher and costlier to the franchise than anything that ever happened on the field. Like the games on the field, there were soon two teams in our office.”

While the ownership showdown was still happening behind closed doors, the swirl of potential coaching candidates filled the newspapers. Among the early names rumored were Joe Paterno, John Madden, George Allen (either as coach, director of operations, or both) and Bill Walsh.

But things were only getting started.

Happy New Year

There’s airing your dirty laundry, and then there’s airing your dirty laundry on New Year’s Eve on the back page of New York City’s largest circulating newspaper.

In the days before YouTube, social media, and 24-hour news channels, the most effective way to get your message to the masses was via the print media.

That’s exactly what Tim Mara did. Evidently, he had a lot on his mind the day he sat down and opened up to the New York Daily News’ Pete Alfano, as his “Special Report” sprawled across six pages over three days. Not a single other tri-state daily offered even a whisper of the turmoil within the Giants’ offices, confirming that this was indeed a single-sourced story.

Featured in the epic saga was a (mostly accurate) history of the Giants’ franchise and its ownership lineage (Billy Gibson and Dr. Harry March are notably not mentioned) and a chronicle of the Giants failures dating back to 1964. This served as a foundation for the second installment where the underbelly of the Giants offices was exposed for all to see.

Both owners were given space to tell their side of the story.

For Wellington, it was personal: “What hurts more is that a whole generation of Maras don’t know (of the Giants glory years).

“Jack and I were unusually close. We worked well together because we had the benefit of our father’s commanding presence. He defined what niches we would fill. Brothers always fight, but there were no major disagreements.”

He also contemplated succession: “I’ve leaned over backwards not to push my kids into the business. I’d like each one to have something to fall back on. John is finishing law school and preparing to go into practice. In a few years, though, well yes, a father likes to think of his son following him.”

An unnamed NFL executive offered some candid insight on the Giants dysfunction, “They have failed to get competent, hardworking people…possibly because of misguided over-loyalty on the part of Well. Andy even complained about his inability to clean (the organization) out.”

Another person with ties to the Giants said, “Tim and Wellington are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Wellington is the kind of guy who orders a beer and a steak sandwich, then goes home to watch TV with the family and is in bed by 9:30 PM. Meanwhile, Timmy is at P,J. Clarke’s handing out Super Bowl tickets to his friends.”

Tim had a more pragmatic philosophy, “I feel the bottom line is what speaks. I believe in results. I’m going to become more involved with making decisions. Time has passed us by. I also feel there is no person in the organization with the football expertise at the present time to get it back on the right track and keep it there.”

Wellington still held the regard of some people within the league. One anonymous executive said, “I think Well is totally competent to run a football operation. He proved it when he ran it under Jack in the 50s and 60s…But when Jack died, he overextended himself…He really did not have competent people under him.”

While lifestyles may have played into the growing rift between the owners, the difference in age between them with Wellington being 62 and Tim 43, may have had an effect as well. Tim said, “I guess I’ll always be ‘the nephew’ to Wellington.”

A huge source of the friction was that while Wellington desired his son John to be his successor, nephew Tim was “next in line.” NFL executives outlined several possible solutions, including Commissioner Pete Rozelle mediating or a court case that would force one side of the family to sell its share to the others.

Wellington concluded, “You get to the point where you say, ‘who needs this?’ Who needs this emotional upheaval in the family? But it’s a personal thing.”

The third, and final, installment saw Tim laid down his gauntlet. Citing the losses of Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi a generation earlier, he said, “This is it. We have to hire a strong director of operations who will come in here and do what is necessary…We can’t make a mistake now.”

Wellington had a different model in mind, “I hope we can hire people who are efficient without being cold. And loyalty is a requisite for being successful.”

After both owners clearly outlined their stances, the organization remained in a holding pattern to nowhere.

An unidentified person close to the Mara family said, “Temperament, lifestyle, and values all contribute to their feud, but it goes deeper than that. It’s in their blood…Wellington was prepared to make changes. He isn’t a stubborn man; he knew what had to be done. But the fact that it was Tim got his back up. He resisted not because he thought Tim’s ideas were wrong, but simply because they were Tim’s.”

Several days later Tim reaffirmed his position to the Bergen Record, “Until recently, I was mainly involved in the building of the stadium and the move to New Jersey. The operation was so spread out – we’d train in Pleasantville and play in New Haven, or train in Pleasantville and play at Shea Stadium. Now, with everything finally settled in under one roof, I can turn some of my attention to the one phase of the team I haven’t really been involved with.”

Regarding the open positions available, Tim seemed outwardly optimistic about the process, despite it running contrary to Wellington’s concepts, “We’d like to get the director of operations named by February 1, then he will choose our next coach. Wellington and I will have to approve his selection, but I don’t imagine that will be any problem.”

Upton Bell, former New England Patriot general manager and son of late NFL commissioner Bert Bell, who had ties with Wellington, said, “There really aren’t that many good job situations around the league, places where you can work without interference with the owners. I do think the Giants’ position would be one of the good ones, though. I think Andy had freedom in his position there, and I think the next man will have the same freedom.”

The next several days saw more names added among the possible choices, including Gil Brandt (who would bring along Dan Reeves as his head coach), John Ralston, Dan Devine, Joe Thomas, and Sid Gilman. Tim told the New York Times, “We don’t think we’re that far away from being a contender. It’s going to take a new team of football management, a director of operations and a head coach to get it out of the people we already have.”

Although this statement was not directly accusatory, it clearly was an indictment of Wellington and the influence he held over the organization as a whole, even if he had taken less of a hands-on role in recent years.

Brandt openly expressed interest in coming to New York: “I think the Giants job is one of the outstanding jobs in professional football. Whenever you have a chance to go to an outstanding organization and an outstanding city, it’s worth taking. I’ve known Mr. Mara and Tim a long time and think whenever you enter into something you do it as partners. It’s the only way to be successful. I think that today everything is so complex that it’s not what one person can do by himself, but what the whole organization can do. I think I could help be part of making the Giants a success”

Round And Round We Go

Wellington, who had remained quiet publicly since the New Year’s articles, broke his silence after Paterno turned down the Giants’ overtures. In doing so, he also revealed his differences with Tim: “I called Joe and told him we wanted to know if he wanted to be considered. I would’ve been interested in having Joe Paterno in some capacity; a man with his record could probably be both a coach and director of operations…It never got to the point where I could actually offer him a job.”

Simultaneously, San Francisco hired Bill Walsh. When asked about his candidacy, Wellington said, “It’s possible we may lose someone we want as coach by picking a director of operations first, but it would be worse if we picked a coach and found out later he couldn’t get along with his boss.”

Shortly thereafter, Dave Anderson of the New York Times was the first to declare publicly a “feud” between the two owners. He quoted Tim Mara, who indicated Wellington had pursued Paterno unilaterally, “I don’t know what job or jobs my uncle offered him. I didn’t ask. My gut reaction is Joe Paterno was never going to come to the Giants anyway.” Anderson concluded by stating that the Giants real offseason priority was not hiring a director of operations, it was getting Tim and Wellington on the same wavelength.

The Bergen Record ran a story several days later featuring the Giants squabbling owners. Staying consistent with his character, Wellington chose to remain as private as possible, “Even if there was such a struggle, I wouldn’t talk about it. I don’t think there is any business where everyone thinks alike. But as far as a power struggle – I don’t think that term is applicable in a family operation like ours.”

Wellington’s dedication to “family” came across as his strongest, and most passionate, virtue. “I remember the first game the Giants ever played in the Polo Grounds. I remember sitting on the team bench; it was on the shady side of the field. I caught a cold, so the next week my mother made my dad move the Giants bench to the sunny side.” The Giants and the Mara family were so intertwined that Wellington made no distinction between the two. They were one and the same.

Robustelli hinted at the changing times and how Wellington hadn’t adapted to the modern business model of the NFL: “It was a totally different setup in the NFL before 1960. The owners controlled the clubs. When Well wanted to make a deal, he’d call Art Rooney or Dan Reeves (owner of the Rams, no relation to Dan Reeves of the Cowboys) or George Halas and they’d make the trade right on the telephone.

“There were only 12 teams in the league then, and the talent wasn’t as distributed as it is now. So, you were pretty sure you were getting a decent player. But then along came expansion, and the American Football League, and things began to change.

“They (the newer teams) turned to organization. They divided the responsibilities so one man didn’t have to handle the entire operation. Then they brought in computers to sort out the talent. They ran their franchises as businesses…The Giants fell way behind. Well just spread himself too thin. He handled everything, from trading, drafting, and signing players to ordering the equipment.”

The next day, the Newark Star-Ledger had Wellington’s response to Darryl Rodgers, who was rumored to be in line for the Giants’ open coaching job. “I understand the problems. The longer it goes, the more ‘experts’ there are. I have heard all the rumors, and I have read all the reports. All I can say is nothing has yet been done.”

He also denied any feud between the owners, “There are differences in opinion, and I suppose there are disagreements. That happens in every family. I don’t know how many times or to what intensity they have to happen to define it as a ‘power struggle.’ As far as I am concerned, there has been no power struggle, there isn’t any now and I don’t expect it to develop in the future. There really is very little power to struggle over.”

Tim said, “I know it’s been mentioned. Everyone had different ideas. For six years we’ve been in the cellar, and I’ve been tied up with the stadium and the lease, the whole move to New Jersey. Now I’d like to be more involved in the football operation. It isn’t really a rift. It’s nothing that can’t be overcome. There’s just a difference in ideas. People have different opinions.”

A few days later, Joe Thomas made the unusual move to publicly declare his desire to be the Giants’ director of operations on the back page of the New York Daily News. Tim said, “A lot of people want to be the director of the New York Football Giants. My uncle and I are currently interviewing several candidates, but no decision has been made, and we haven’t ruled out anyone.”

The next day Tom Landry publicly endorsed Dan Reeves for the Giants coaching position: “Any man who can run my offense can survive as a head coach.”

Neither owner would confirm or deny any potential candidate.

Tim said, “We are still conducting our search. We are not going to reveal any names, or the number of people we’ve talked to, or if we plan to talk to anyone else. But we still want to come to our decision as close to our deadline as possible.”

Wellington said, “It’s taken longer than I expected.”

Giant veteran Doug Kotar offered a player’s perspective on the ongoing search. “I can see why it’s taking them so long, they have an important decision to make. I’m sure they don’t want to make a mistake. And I know you can’t just go out and pick a guy. You have to find out who’s interested, and who you’re interested in. But once a coach is named, he’s going to have to name a staff. Then he’s going to have to teach all the players a new system, and that takes time.”

Quarterback Joe Pisarcik added, “Sure, I’d like to find out who’s going to be the coach as soon as possible, but I don’t want to see them rush just to get it done quickly. It’s only a few days after the Super Bowl, and while they can’t drag this thing out until June, they still have time. I’d like to see them get a coach with great credibility who will get the confidence of the team right away.”

Several days later NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle revealed he’d been in contact with the Giants in an attempt to resolve their struggles. “I have talked with both Wellington and Tim, individually and together, during the past few months. I offered some suggestions on people they might want to check out for the D.O. position. I am now happy they’re working to find the man they both feel will be in the best interests of the Giants.”

Bunker Mentality

Unfortunately, the dysfunction of the Giants organization was not self-contained. A peculiar move had a ripple effect beyond the Meadowlands that made some with close ties with the Giants family uncomfortable, possibly affected their credibility around the league, and most certainly ratcheted up the tension between the ownership factions.

While the full story unfolded over several weeks in the press, the short version is this: on the recommendation of Tom Landry—a former Giants player and coach, and a longtime friend of Wellington—Cowboys scouting director Gil Brandt and assistant coach Dan Reeves were made available for interviews by Tex Schramm. With the ownership stalemate showing no signs of easing, Wellington unilaterally interviewed Reeves without informing Tim.

Regarding the mood internally, one unnamed Giants’ staff member said, “The iron curtain has descended.”

While that was going on, the front pages latched on to a new name, Dan Klosterman of the Rams. Wellington and Tim offered up the usual denials and generic non-answers, but Rams’ president Carol Rosenbloom confirmed Klosterman’s availability and backed it up with an endorsement.

Klosterman did officially interview with the Giants, however an agreement was never reached. In fact, on the day the interview was reported, Tim mentioned Gil Brandt as still being a strong candidate. “We have had several interviews, two of which were made public. The people we have interviewed are very impressive, with sound philosophies in football. There are people available this year, people who have been around before but haven’t been available.”

The Giants released Larry Csonka on February 1.

Instead of being a strictly football-related move that would provide respite from the daily bickering of the owners and rumor-mongering of who was interviewed for what position, Tim attached an I-told-you-so addendum to the exit: “I think Larry is a terrific person, but how much did he help the Giants, and how much would he in the future? I would have never taken Larry Csonka. I felt that at that time we were in another rebuilding year. We had a young team and Larry Csonka was not a good investment for the Giants.”

He also offered a cryptic update on the status of the two open positions, “Well is taking his time, making sure to look into everything. Of all the candidates we interviewed I objected to only one. We probably will not interview any more candidates. I don’t think it’s necessary to interview anyone else.” He did not name the candidate he was opposed to, but the running speculation was that it was the Giants’ own internal candidate Terry Bledsoe, who was a Wellington hire.

Vinny DiTrani of the Bergen Record ran an article detailing Tim’s tenure with the Giants since his ascension with the Giants Stadium project. Within the story, he detailed the major points of friction between Tim and Wellington. Aside from the already-known Csonka signing, there were issues with offensive coach Bob Gibson’s firing the day after “The Fumble,” Wellington’s hiring of Terry Bledsoe earlier that spring, and the hiring of an offensive line coach in 1976 when Tim had wanted Ray Wietecha but was overruled. Most interestingly, DiTrani cited what had been an unknown instance where Tim did persuade Wellington to acquiesce in his favor. Following the disastrous 1973 season where team morale was at an ebb, Wellington was on the verge of re-signing coach Alex Webster. Tim intervened and convinced Wellington that it would be the wrong thing to do. Since then, however, it appeared that Wellington had continuously shut Tim out of all football decisions.

Not long thereafter, Tim made the headlines again when he bluntly stated his increasing frustration, “We are starting to look foolish. We both realize we are hurting the team, and that we need to get this thing settled. I can say I think we’re finally on a constructive course, and I couldn’t say that at all last week. I was very frustrated last week… (the delay in hiring) shows when we can’t reach a decision that we are not very professional…We’ve been in the cellar five of the past six years. How much worse can we get?”

Tim also denied that John Madden had turned the Giants down for one or both of the roles. The Newark Star-Ledger speculated on a whole slew of names, including but not limited to Ernie Accorsi, Hank Stram, Dick Nolan, Tommy Prothro, and George Young.

While the stalemate lingered and rumors swirled, Rozelle drafted a document forbidding any future 50-50 franchise ownership – though there would be a single voting partner, which was Wellington as president. From that point forward, one partner must control at least 51 percent of the holdings. The Mara feud continued, but Rozelle had already had enough. Wellington lamented years later: “I regard it as a personal tragedy that our club provided the wisdom for that rule.”

Regarding the current state of unrest, NFL executive Don Weiss said, “I’m sure Pete would be willing to sit down and work with them in attempt to settle their problems. He’s already indicated that, but I’m sure he won’t intervene without the request of the Maras. The Giants have always been one of the leaders in the area of league tranquility.”

Giants’ linebacker Harry Carson provided a delightful moment of much-needed levity from the oppressive drama that the Giants had been mired in for nearly two months when he offered his services for the coaching position. “I’d like to be the coach myself, they should consider me. Let the players coach for a year; see how it would work out. I bet it would work out pretty good. The players know what they want to do, what works on the football field…The players know the players better than the coaches do. I hope they hurry and pick a new general manager, I want to go in and negotiate.”

While everyone enjoyed a good chuckle with Carson’s clearly tongue-in-cheek proposal, no one had any idea that the mouth of the abyss was widening, threatening to swallow the entire Giants’ organization into perdition.

Welcome To The Shit Show

The lasting shame from the morning of February 9, 1979 is that none of the hastily-assembled media who responded to Wellington Mara’s surprise press conference, called on 60-minute notice, brought a TV camera. Probably because what was billed as a briefing on the coaching and director of operations search was expected to be another mundane gathering in which rumor denials and non-answers were regurgitated ad nauseum. All we have are the print reports from the astonished reporters and editors. Reporters eagerly chronicled the theater of the absurd they had witnessed, but imagine how much more captivating it would be to relive it endlessly on YouTube today. Dueling owners held opposing press conferences, taking public shots at each other—unfiltered and unrestrained—completely abandoning decorum and protocol. It was owner vs. owner, uncle vs. nephew, president vs. vice president. The spectacle was unprecedented. The family’s dirty laundry was aired for the entire world to see.

Several writers quoted multiple anonymous Giants’ employees who stated this was the franchise’s lowest point, even beneath the infamous “Fumble” that had set all this discord in motion less than three months earlier.

Wellington spoke first, in what pretty much followed the expected form. However, Tim was lurking, not unnoticed in the background, likely seething at what he was hearing. After Wellington concluded his statement and left the pressroom for his office, Tim stepped up to the podium and ad-libbed a response that contradicted everything Wellington has said, complete with unveiled snide commentary and direct accusations of incompetence. After Tim exited, the press requested Wellington’s return for a rebuttal, to which he obliged.

It was also revealed that Wellington had conducted his own clandestine search for a coach (Dan Reeves), despite not having a director of operations in place.

Among the highlights:

Wellington:

- “There’s no way I’d want to become director of operations. I don’t want to return to the front lines, especially when I don’t know from which directions the bullets are coming.”

- “Tim only wanted to be consulted on the major decisions. But I didn’t think anyone who didn’t participate in the smaller everyday decisions was qualified to be in on the major decisions.”

- “It’s apparent to me we’ve got to get the best man available to run this team. Our only area of serious disagreement is over the director of operations. Until we can find someone to accept this job, I think we should find a coach and put him in charge of the football operations.”

Tim:

- “I just found out about this an hour ago. This is no way to run things.”

- “Well says he wants to have a winner. Well wants to have a winner Well’s way, and Well’s way has had us in the cellar the last six years…If we do that, we’re back where we were 15 years ago.”

- “I have asked Well not to proceed with the selection of the coach until the director of operations is chosen. The coach is only one part of the football operation. The director of operations pulls it all together.”

- “The people Well’s in favor of have been linked only to failure.”

The slack-jawed assembly left Giants Stadium more puzzled than ever, and with a deeper level of concern for the now apparently crumbling franchise. Several editors openly pleaded for Rozelle’s intervention to save the Giants from themselves.

Unbeknownst to most of those present, the commissioner had already been intricately involved. Wellington said, “Rozelle asked both of us to submit four names acceptable to us as director of operations. I submitted my list Monday and was informed the second name on my list also appeared on Tim’s list (later revealed to be NFL executive of player development Jan Van Dueser). We were in communication with him Tuesday and Wednesday. He told us he did not want the job. He didn’t say so specifically, but I definitely got the impression he didn’t want to become involved in the current affairs of the front office here.”

Most clearly, the Giants owners’ dispute ran deeper than who to hire first, the coach or director of operations. They were embroiled in a power struggle complicated by family dynamics and were stuck at an impossible impasse that showed no signs of resolution.

Tim said, “The signing of the coach must meet the approval of the board of directors. It’s my contention the president serves at the will of the board of directors…I’m going to take this up with the commissioner.”

Wellington asserted his belief that he was the unchallenged decision-maker of the Giants: “I don’t need the approval of the board of directors. As president, I have the power to move on such matters. Those powers are spelled out in the New York State law. Sure, we could go to court over it, but I don’t know how that would benefit the Giants…I think I’m safe unless my son rats on me….We’re a family but the president has the power to act. I will hire a coach.”

The mood was so bleak that Giants’ PR director Ed Croke said when asked if he could step in as director of operations, “I wouldn’t take the job.”

Everyone in the NFL was fixated on the happenings at the Meadowlands. One unnamed general manager said, “A team that has given its fans bad memories has to do something to renew hope. The Giants should get their new people, expose their ideas and show their faces. New blood tends to get people excited, and this is the time to get that kind of positive publicity.”

Another league executive said, “They need somebody competent who can act in behalf of their club. Right now there is not really anything positive in the Giants delay.”

Eagles’ general manager Jim Murray said, “Nobody knows the real situation when you’re looking in. You have to get the guy who best fits your operation, and it can’t be an emotional decision. The Giants have twice as much at stake.”

An anonymous NFL owner dissected the squabble to its core: “These things go on all the time in pro football. And the important thing to remember is that they have nothing to do with winning or losing. They are only about power. Nothing else.”

When Rozelle was asked for comment, his reply was, “I have nothing to add to it right now.”

The Day After

Rozelle may not have anything to say, but New Jersey Governor Brendan Byrne did.

They day after the dueling press conference fiasco, Byrne announced the State’s intention to purchase the team from the Maras. “The Meadowlands sports complex is first-class, and a professional operation and New Jersey had expected a similarly professional performance from the Giants. I’ve asked former Attorney General William Hyland, the chairman of the sports authority, to look into possible alternatives…If (the Maras) want, we will help find a buyer for them, either from the private or the public sector.

“There is a sense of frustration among Giant fans who are so dedicated to this team. They are entitled to something better than this ridiculous dispute.”

Hyland said, “It is unfortunate that we cannot come into court on the ‘deadlock statute’ and have a receiver declared for the Giants club. But this thing affects the public interest. If the problem affects attendance, the state, as landlord, would suffer. So, we are looking for actions to act upon.”

Tim continued his media campaign, once again promoting George Allen—Wellington’s least favored candidate—for the head coaching job. He also revealed that he had learned of Wellington’s secret pursuit of Dan Reeves. While Tom Landry tried to mediate between the feuding owners, other former members of the Giants’ extended family began to voice their own opinions.

Alex Webster said, “This is a very disturbing thing for me. The Maras washing their linen in public. It’s incredible.”

Robustelli said, “I certainly am sorry to see what’s going on right now. It is difficult to say if Well and Tim will work things out and be back in good graces with each other. Like a lot of quarrels and a lot of love affairs, some end up good and some bad.”

Jan Van Dueser stepped forward to identify himself as the candidate who rejected the director of operations job, “They made me a very generous offer and it’s a fine job with a lot of opportunities. But it’s just not for me at this time. I have no plans to reconsider.”

The dissection of the dispute continued for days. Dave Klein of the Newark Star-Ledger presented a very pragmatic overview of the situation and why the solution would not come easy.

“Section 8.3 of the NFL’s Constitution and By-Laws would allow this intervention, It reads:

”’The Commissioner shall have full, complete, and final jurisdiction and authority to arbitrate any dispute involving two or more members of the league, or involving two or more holders of an ownership interest in a member club in the league, certified to him by any of the disputants.’

“In this case, ‘any of the disputants’ might also be interpreted as the other two members of the board of directors. Wellington’s 23-year-old son, John Kevin Mara, a law student at Fordham; and Mrs. Helen Mara, Tim’s mother and widow of Jack Mara, Wellington’s brother. The problem with a four-person board of directors (Wellington and Tim are the other members) is that there is no provision for breaking a tie vote, and these four are very obviously split, irrevocable so.”

Klein quoted an anonymous NFL office executive: “What the commissioner really spends most of his time doing is trying to mediate and arbitrate disputes and disagreements without really taking sides.”

George Usher of Newsday shed some light on Reeves and his peculiar role in the overall plot. Reeves said, “I haven’t heard from them, but I do hope they call me in this week for a real interview. I don’t know if the thing with Tim will hurt me, or not. I was put in a bad spot. I was told by Well not to say anything, and assumed he didn’t want it in the papers. If Tim is holding it against me, I wouldn’t want the job.

“If (the feud) is not resolved, I won’t take the job if it is offered to me. It’s tough enough in the business to win when everybody in the organization is pulling together. If it’s going in opposite directions, it’s impossible to win. But I’m just waiting to hear from them.”

While the stare-down between Wellington and Tim showed no sign of movement, a surprising number of former Giants’ players and employees chose a side.

An in-depth article in the New York Times featured a diverse array of voices, each with varying opinions.

Al DeRogatis said, “He had no alternative. What options does a mature Tim Mara have? To sit back and watch the parade until the stands collapse under him? He just wants to be heard. He’s doing what I damned well would’ve done 12 years ago,”

Pat Summerall said, “(Tim) chose to stay in the background because he thought the ship was in good hands. One guy has been running the ship, and the ship isn’t holding up. You can’t keep living off 1956 and 1963. The fundamental difference is – your way isn’t working. It’s appraisal of talent. They disagree. He’s not doing this to hurt Wellington. Tim is a very intelligent man with a shrewd sense of business. They could do a lot worse than just give the team to Timmy and say: run it.”

An unnamed acquaintance of Wellington said, “What the hell has (Tim) done except second guess from a booth at P.J. Clarke’s? If Tim ran this club the Giants might not even be in the league in a year.”

Former Giants’ PR officer Don Smith said, “A younger, more formidable Well Mara wouldn’t have stood for this. Never in million years would Timmy have challenged Well 10 years ago. Timmy was more afraid of Well than he was of his own father. Timmy would have backed down in 10 seconds. But Timmy hasn’t backed off, and Well hasn’t prevailed. It may be that Well is battle fatigued…The inviolate Mara bond has come apart. Blood was always thicker than water. The sense of family is being disrupted, shattered in the press.”

Art Modell said, “Well Mara has been Mr. Football in New York, and he should continue to be. The hell with 50-50. Well should be running this thing…He is terribly, terribly hurt and grieving.”

Wellington Mara poignantly stated, “I’m 62 now. I won’t be around forever. I want a man who can run this franchise for the next 10 or 20 years, a good man whom I can trust. I feel as though the Giants are the Mara family heritage; I think they represent the life’s work of my father and brother. They left it in my care, and it’s slipping away. If the Mara presence is eradicated under my regime, and I couldn’t stop it, it would be a terrible thing.”

He also hinted that there was division throughout the Mara clan, as his children had aligned against Tim, “It is there, and I wish it were not…I think there’s a difference between an equal voice and the ability to immobilize an organization. I think Tim blames me for everything. I feel badly, but I feel worse that there is an opportunity and reason for him to do so.”

As far as Wellington’s influence on the Giants organization, an anonymous employee said, “Well’s personality and authority and dominance of the Giants was such that even when he delegated authority, people wouldn’t take it. People always deferred to him. He intimidated people without meaning to.”

Each owner offered some personal insight into their disagreement.

Wellington inferred of Tim, “Maybe the lifestyle is an indication of different values rather than a cause of incompatibility.”

Tim said, “I’ve lived that way for 20 years now, and I don’t think it’s a major factor. It may be that Well is a little jealous of me now because of (Giants Stadium). It’s the best thing the Giants have done in 15 years. Nobody ever hung me in effigy. Nobody ever said, ‘Get rid of Tim Mara.’ I think we’ve deferred to Well long enough.”

Wellington’s son John said, “The most disturbing thing is that we’ve prided ourselves on being a family. We’ve always been able to work things out, and now we can’t.

“Tim looks at the record, and he has a point. But my father accepted all the blame. Timmy was in agreement with a lot of the decisions in the last five years, but he shows no willingness to admit it. All he does is blame my father. And now he’s a hero to the media. It’s pretty much torn the families apart. It’s unlikely that we’ll ever be able to live together peacefully again.”

The Intervention

Pete Rozelle probably never envisioned himself becoming a family counsellor when he took over as NFL Commissioner, but with a situation as sticky as the one the Giants were in, with family and business so intertwined, he had no choice. Ever the diplomat, Rozelle said when asked what he could do to bring the turmoil to a close, “I’m going to continue working with them. But the less said, the better. I want to help the situation rather than worsen it in any way. I just want to see it resolved.”

Ironically, the men with the broken hearts convened in the NFL offices, if not to mend their personal relations, at least arrive at a truce in their business dealings, on Valentine’s Day.

More poetic the circumstances could not be.

The morning of the summit, Rozelle played it as low-key and neutral as possible, “It’s a continuation of the meetings I’ve had with them over the past few months. It’s just another part of my effort to get them to work it out between themselves.” He also demanded they keep their comments out of the press, “I think it creates friction between them and makes it difficult to get candidates with all the glare and publicity. We’re going to meet today to go over some of the names that have been mentioned and offer some new names.”

The meeting included a fourth member, George Young, who the two owners had met in regards to the director of operations position with earlier in the day on the recommendation of Bobby Beatherd, as the two had worked together under Don Shula in Miami.

Tim Mara recalled: “…we go on Wednesday to the Drake Hotel, and we interview Young for two hours. We’re impressed and we go to Rozelle’s office. We’re sitting there and we have to go over the new resolutions about how the club shall be governed and who has right of first refusal in the event of a stockholder’s death and things like that. It also placed the football operation in the hands of whoever would get the general manager’s job.

“George wants to go home and talk it over with his wife, but Pete wants it settled tonight. So, George is in the other room and we’re dotting i’s and crossing t’s…Now it’s like 7:00 p.m. and nobody is in the league office, so Pete walks over to the typewriter, and he starts to type out the press release for that night. It’s probably the first one he wrote in 25 years and the last one he ever wrote. While he’s writing, he suddenly looks up and says, ‘This is a great way to spend today. It’s my wedding anniversary.’”

Dick Lynch, former Giants player and then radio broadcaster said, “You won’t hear from Tim again as long as the team improves and gets to the playoffs soon. He’s just like his father. He’s just like Jack. He just wants to have a good team.”

Perhaps accentuating that point, along with a subtle claim to victory, Tim said, “Young is a Brandt-Klosterman type,” insinuating the hiring suited the criteria he had pushed for.

Wellington, predictably, was more diplomatic. “George’s powers are spelled out in his contract…I’m satisfied with the way things went. When you have two people, you have no problems when they agree, only when they disagree. I said the one major disagreement we had was with the director of operations. Now that’s over. The scars? Time will tell about the scars…I don’t think anything will occur that will affect the operation of the team. But as a family, that’s another matter.”

An unnamed Giants’ employee lamented, “(The public feud) couldn’t have happened any other way. It was there. It was going to come out.”

When asked about succession now that the 50-50 ownership was recognized as being an equal partnership, Robustelli said, “Wellington wants to perpetuate the father-son thing if it’s at all possible.”

Wellington’s oldest son, John, 23, said, “Sure, I’d like to run them someday.”

For Tim, the matter appeared to be settled: “Now that the general manager and coach have been chosen, I’ll go back to my end of the club – the business end. I don’t think Well and I will have any serious disagreements in the future. We’ve had very few anyway.”

Winning Doesn’t Cure Everything

The scars Wellington alluded to never did heal. Despite the Giants on-field performance drastically improving through the course of the 1980s, their most successful decade since the 1950s, the uncle and nephew never returned to speaking terms.

Young said years later: “I had worked for Carol Rosenbloom, Joe Thomas, Bob Irsay and Joe Robbie, so I knew a little bit about these situations. Compared to those guys, the Maras were choirboys.”

A Giants’ employee said: “(Young) must be the only person in the world who can command the respect of both Wellington and Tim on a day-to-day basis. He’s a little more firm with Tim than he is with Wellington, but he gives them both the impression they have major input into all decisions. They don’t really, but the important thing is he makes them think they do.”

In the midst of his second season managing the Giants football operations, Young told the New York Daily News in December 1980, “I have more control over the football operation than most of the general managers in the league. I have fewer restrictions than easily three-quarters of them. Every executive in the United States has to answer to a board. I have more power than most executives in the United States.”

Rozelle’s assignment of power and responsibility proved to be fortuitous, as several persons with close contact to the Mara’s described the tensions within the front office as being as bad as ever.

Robustelli said, “I can tell you it’s not a good situation.”

An anonymous employee said, “The front office is divided into two camps. Some people in the front office have sided with Wellington and some have sided with Timmy. The break has never healed. It’s worse than it was. It’s a lack of communication. Hostility. Animosity. I think they may well not talk to each other.”

Tim confirmed their statements, “I’d have to say that’s correct. Our differences don’t affect the ballclub. And they shouldn’t. And they haven’t so far.”

Upon the Giants first playoff qualification in 18 years in 1981, both owners were asked if their relationship had improved. Tim said succinctly, “No, sad to say.” Wellington implied the same, if indirectly, “I’d rather not talk about it. It’s family. Obviously, it’s not affecting the performance of the team. As long as George Young is able to do his job, I don’t think the rest is that important.”

Tim offered his opinion on why any grudge may be persisting, “The whole thing we went to war over three years ago is that he, although he is president, doesn’t have complete authority. He just can’t accept that this is a 50-50 deal…Maybe it’s because he sees that this arrangement has accomplished in three years what he couldn’t in 15.”

There may be some truth to Tim’s assertion. According to Ron Fimrite’s article in the January 18, 1987 Super Bowl XXI preview issue, Wellington had made an attempt to get some of his lost power back, despite the Giants having become a playoff regular under Young’s stewardship: “The Maras have other problems. At one point several years ago, Wellington wanted Commissioner Pete Rozelle to adjudicate the differences between the 50-50 owners in the hope of restoring some of his lost authority. Rozelle refused, so the nephew and the uncle and their respective families remain uncomfortable bedfellows: Wellington as team president, Tim as vice-president and treasurer. So strong is their mutual aversion that each has erected a separate barrier between their adjoining luxury boxes…Young, meanwhile, runs the team with crack efficiency, although the Maras do have veto rights over head coaches, first round draft picks and major trades.” The New York Times confirmed this and placed the event in March 1984. When asked, all Wellington said is, “I didn’t know this correspondence was public.”

As always with Wellington, the Giants were a more personal thing than a business, as he said to the Bergen Record in August of 1986, “The team is a family business. It is not just a plaything or something we do for the sake of ego. Many football teams face the possibility of not making a great deal of money. For family-owned teams, that would present a real problem because this is our primary source of income…The team has been the family business for 60 years, and hopefully it will always be the family business. I just can’t imagine what it would be like without it.”

Young, then in his eighth season as general manager, described their relationship, “Workable. Sometimes it’s awkward, but it’s more the fact it’s 50-50 deal than any feud. It requires me to adhere to protocol and touch all bases. It’s by no means a nirvana, and from time to time it’s uncomfortable. But that’s minimal…I’ve been to a lot of league meetings and I’ve seen all the other owners…That feud thing is overplayed.”

John, now 31, said, “If I think we’ll ever sit down together for Thanksgiving dinner or Christmas, I’d have to say no, probably not. But I really don’t think the situation is that bad. It’s been seven or eight years since the thing became public, and just because we don’t get along socially does not mean it affects the team. I think too much is made of the feud.”

Both owners heaped praise on Young and the job he had done.

Wellington said, “I don’ think the family problems have hindered the running of the team. And credit for that must go to George. He is a good diplomat. He has handled things skillfully, always having to put out trial balloons. I’m sure it has made his job harder and put a strain on him at times.”

Tim said, “George has done his job very diplomatically, and very well. He knows the system and he has a good understanding that neither side has good control, that it’s 50-50. I’m sure there is a little more pressure on him…It’s too bad we had to go through it, but I am happy with the results…It just proved what I said was right. We had to get someone in here who knew what he was doing…It’s just too bad some people had to be offended by what happened.”

Regarding the differences in lifestyles, he said, “I won’t deny it. I like to play hard, but I figure if you work hard you’re entitled to play hard. I like to travel. I don’t think I have to be (in the office) nine to 12 hours a day. But I know what’s happening all the time.”

For Wellington, the theme of family was ever present, “(John) is intelligent, always done well in school and in the legal business. Although he hasn’t been as exposed as much to the team as I was at his age, I see he has a feeling about the team and the same kind of values I had on how it should be run. I can see a lot of myself in him, and I think every father likes to see that in his oldest son…John has never told me in so many words he would be willing to take my place, but it has sort of been a tacit agreement between us.”

John said, “My father and I still do not have a specific time set for me to join the team. I’d prefer to make the move while my father’s still there. That’s certainly something I have hoped for all my life, to work with him…But if I were to go over there now, I don’t know if I would meet resistance from the other side of the family. If I moved someone out of a job, I’m sure that would face resistance. And if a position was created for me, then there probably wouldn’t be much for me to do…The way the team is run has changed so dramatically, I’m not positive what my role would be.”

Tim closed by saying, “We haven’t had many big problems since 1979, nothing out of the ordinary. But we had so many before that. I hope we can continue on the same track we’ve been on the past two years. It has been like a dream come true. Now we just have to go a little further and make it to the Super Bowl.”

Newsday published a feature on George Young where Tim’s praise of the general manager also justified his position in the feud: “I don’t know if you could be worse than total destruction, but that’s where we were headed in 1979. We had no idea what it took to win until George got here. We were firing coaches in mid-season, bringing in players who were washed up. We were accepting losing. My idea was to get a football guy in here and let him run the damn thing.”

Young said of the two owners, “I don’t find they’re so diverse. There’s a generation-gap type of thing there, but if there’s a problem of a sensitive nature, both of them are very giving…They’re two very fine men. They just happen to be Irish.”

Near the end of the article, Tim cryptically mentioned overtures he had received on selling his share in the franchise, “I hear offers. I’d say I get about two a year. It never hurts to listen, but I don’t think right now I have any interest in selling.”

The Giants finally reached the Super Bowl and ended their 30-year championship drought in dominant fashion. But the nation also caught a glimpse of the franchise’s internal discord when the team’s owners received the Lombardi Trophy separately—first Wellington with coach Bill Parcells, then Tim with George Young. Fans outside the tri-state area, unfamiliar with the strained relationship between uncle and nephew, were likely left puzzled by the unusual proceedings.

In fact, on the eve of the Giants divisional playoff contest against San Francisco, both owners were quoted in a lengthy article on the history and aftermath of their feud. Wellington was steadfast in his contention of being wronged: “I don’t wish to discuss family matters. What Tim did, did no good. We’d be the same today.”

When told of Wellington’s comments, Tim was incredulous, “It is ridiculous and unbelievable that he would make such a statement. The incredible thing is that he really tried to make himself believe it.”

Young reasserted his role of a power-wielding diplomat, “I’m an employee and that’s all I want to be. It’s their property and they have every right to be consulted. I can tell you, though, that they have gone along with me. They never said no, and I think that’s because they know I have the good of the franchise in mind.”

Tim: “There has to be a system to adhere to; that’s why I fought so hard for what I believed in back in 1979. I just thought time had passed us by…It took a little while…We had to decide on resolutions by which we would run the team.”

Wellington: “I wanted George to inform me of any major player or coaching moves. And I wanted to feel free to give my opinion. I still went to practice and kept in touch with what was going on personnel wise. But George was the one making the decisions.”

At Super Bowl XXI presentation Tim said, “We’re co-owners, but Well’s the president, I understand.”

Those close to the Giants were disappointed that the ultimate prize did nothing to soften the stance between Tim and Wellington.

Art Modell said, “Somehow, some way it must be corrected. They don’t even talk. It’s a terrible situation. But they’ve won despite that. Maybe you’ll say giving George Young the supreme power is the answer. But I wouldn’t like it, with relatives, particularly when they’re Irish.”

A Mara family friend said, “Everybody has tried to make peace between them but nobody has succeeded. It’s a shame, really. We were praying the Super Bowl victory would finally put an end to it. But, if anything, it may be worse.”

Tim told the New York Daily News in July 1987, “We don’t communicate, and we don’t need to. It would be nice if it were different, but you have to face the facts.”

In the four years between Super Bowls, there was very little revisiting of the feud and Tim’s name scarcely appeared in print. Wellington’s only commentary pertained to the state of the Giants or league business. From the outside, all appeared tranquil.

The owners typically brushed away any questions in their usual manner, either by deflection or by minimizing.

Wellington: “It’s a hurt, but one I don’t care to discuss. It’s a personal, family thing.”

Tim: “I’m used to it. It was painful at the start. I go about my business.”

For most observers, the sale of Tim’s 50 percent of the Giants in February 1991, less than a month after the dramatic victory in Super Bowl XXV, was a shock. To those on the inside, it was probably less so. The tension between Wellington and Tim never eased. According to one source, Tim began sending out feelers for potential buyers as early as the fall of 1989.

The outcome was likely inevitable, given the seemingly unresolvable conflict between the families. The real surprise is that it took 12 years to come about.

For Tim, “The time just felt right.”

While outwardly Wellington stopped just short of appearing jubilant, he did confess, “A certain tension was relieved. Let’s put it that way.”

Only four years after selling his share of the Giants to Bob Tisch, Tim passed away at the age of 59 following a battle with Hodgkin’s disease.

After Tim’s passing, Frank Gifford recalled the meeting he had arranged where the estranged uncle and nephew made an attempt at reconnecting in 1994: “They hadn’t been communicating. They had totally different lifestyles. It was a very cordial meeting, something both of them wanted. The two shook hands. They never really got around to talking about what had happened in the past. But they talked about the team, many things…I think it would have taken a while, primarily because their lifestyles were so different. But I think they would have gotten back to being what a family should be again if Tim hadn’t gotten ill.”

Remaining true to his character, Wellington’s public statement was polite and reserved, “A death in the family is a personal thing and I would just ask people to respect my privacy at this time.”

George Young said, “He really made a great contribution to the team and the franchise when he was here.”

Since 1991 the Giants have been run by the Mara and Tisch families in very much the same manner as they have since 1930 when Tim Mara I passed on the franchise to his two sons Jack and Wellington. The Tischs handle the business and marketing side of the business while the Maras run the football operations. Wellington and Bob Tisch both passed away just weeks apart during the 2005 season, and their respective sons John and Steve continue their legacies today.

While Tim chose to sell his share of the Giants, his legacy to the team lives on.

Sources:

“1947 New York Football Giants Press & Radio Guide”

n/a 1947 New York Football Giants, Inc.

“1966 New York Football Giants Press, Radio & Television Guide”

Don Smith 1966 New York Football Giants, Inc.

“It’s Just One Man’s Family”

Robert H. Boyle Sep. 25, 1972 Sports Illustrated

“1978 Giants Media Guide”

Ed Croke 1978 New York Football Giants, Inc.